A MERE 1,682 social homes were completed in the 2018/19 year in Northern Ireland. It nowhere near meets demand.

The social housing waiting list in Northern Ireland contained 37,859 applicants at March 2019. At the current rate of house building it would take 22 and a half years to build enough homes to meet the demand. Except, of course, many of the applicants currently on the waiting list would have died in the meantime. To put it another way, the social housing sector would need to grow by nearly 30% to accommodate all those on the waiting list.

What is particularly concerning is that 26,387 of the applicants at March 2019 were recognised as being priority cases, where people were in ‘housing stress’. It would take 16 years at this rate of new building just to clear the priority cases. And the number in stress is rising – it has increased by more than four thousand since March 2015. Worse still, 19,629 households were accepted as being homeless in March.

These figures represent a social housing crisis of too few homes being built. It is made much worse by a political dispute over the future of the Northern Ireland Housing Executive – a row that it seems cannot be resolved while the Executive and Assembly do not function.

There has been a debate taking place for several years about how to restructure the Housing Executive to enable it to build many more new homes. While housing associations own about 42,300 units of social housing in Northern Ireland, this is dwarfed by the number owned by the Housing Executive – over 85,000.

The Housing Executive is a non-departmental public body, sponsored by the Department for Communities. As such, its capital spending is subject to public sector controls. There has been discussion for several years about the Housing Executive being reconstituted as a housing association to enable it to borrow on the capital markets and build many more new homes.

But even when the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive were functioning, it was impossible to achieve political consensus about the Housing Executive’s future. Discussions focused on whether it should be converted into a single, massive, housing association; broken up into new regional housing associations; or sold in part or whole to an existing housing association. The political ante was increased because some parties argued that housing associations, despite being unable to create distributable profits, are private sector bodies and that any change to the constitution of the Housing Executive would constitute privatisation. (That argument is aided by the sometimes very high salaries paid to senior executives in housing associations.)

This stalemate is especially frustrating as Prime Minister Theresa May has substantially increased funding for housing associations in England, enabling them to accelerate their building of new homes. Late last year she agreed that funding to English housing associations would move onto a more strategic and longer-term basis, backed by £2bn of additional money. Through the Barnett formula, a pro rata amount is provided to the devolved nations. Until recently, an arcane problem relating to the statistical treatment of housing associations in Northern Ireland was holding back their capacity to build more homes. That issue has now almost been resolved, but without an Executive it may not be possible to approve extra money for housing associations.

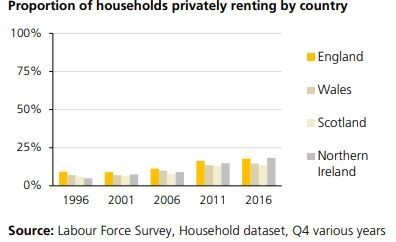

Another profound change is taking place in the housing market – the privatisation of rental accommodation. In both Northern Ireland and England, there are now more homes for rent in the private sector than in the social housing sector. (By contrast, in Scotland 24% of homes were in the social housing sector in 2016, compared to 13% in the private sector.) Northern Ireland has witnessed the sharpest increase in homes for private rental of the UK’s four nations.

As recently as 1996, a quarter of Northern Ireland homes were in the social housing sector. Today it is 16%. Over the last 25 years, Northern Ireland has seen a significant growth in the private rental sector – it was negligible in 1996. This change reflects, in particular, the number of properties purchased by tenants under the ‘right to buy’, many of which have since entered the private sector rental market. By 2016, about 19% of the total housing stock in Northern Ireland was privately rented, according to analysis by the House of Commons Library.

There are several reasons why this shift from the public to private sector is to be regretted. A recent study from the Local Government Association looked at the impact in England of the decline in social house building, including council housing. It found that whereas in 1997 more than a third of households in England lived in council housing, the figure is now just one in ten, while the number of new social homes being built in England fell from more than 40,000 in 1997 to a mere 6,000 in 2017. A small amount of new council house building will now be permitted, funded by borrowing, the government announced at the end of last year.

Rents in private housing are significantly higher on average than in social housing. As a result, in England, taxpayers have had to subsidise rents through housing benefit to the extent of an additional £7bn in the last decade. At the same time, tenants not on housing benefit are paying much more for their rents, too.

The Nevin Economic Research Institute has urged Northern Ireland policy-makers – to the extent that at present we have any – to increase the supply of social housing. It observed that “the evidence does show that there is a considerable shortage of supply of social housing in regions where demand is highest”, adding that “a lack of supply of social or public housing is forcing people into housing tenures that bring them into poverty”. It called for the reclassification of the Housing Executive as being outside the public sector, thereby freeing it to build substantially more homes. This, in turn, would reduce household poverty, cut the cost to government of housing benefit and stimulate the economy, creating jobs.

It is a similar argument to that made in England by the Local Government Association in pleading for more council house building there. And it makes equal sense.

Paul Gosling is a freelance journalist, commentator and author, and 'Brexit expert' for the Holywell Trust charity. His books include 'A New Ireland: a ten year plan', 'The Fall of the Ethical Bank' and 'Abuse of Trust', which he co-wrote with Mark D'Arcy. He can be found on Twitter @PaulGosling1

Click here to return to the second of The Detail's special two-day report on social housing in Northern Ireland which explores the Social Housing Development Programme.

- A note on statistical sources. The official housing statistics of the Department for Communities use different figures from those used by the House of Commons Library and also those quoted by the Northern Ireland Housing Executive and the Northern Ireland Federation of Housing Associations. We have used the most credible statistics in each case.

By

By